Conference Conference

Oct 28, 2024It’s not that I’ve been lazy! I’ve just had nothing to say! Or no way to say it. Conferring with my peers helped me break the spell, and out gushes the nonsense. Let it flow! The good stuff is in the garden, anyway.

Within you will find:

- incomprehensible rants about software and academia

- ineffectually brief and noncommittal book reviews

- inconsistent typography

Enjoy?

# Scoop me

SPLASH 2024 got me thinking about the research questions I wish I had time to investigate. I feel an undeniable compulsion to write them down here so that someone can please please explore them, because I need to see the results (and the field needs it too)!

Games for teaching programming

Programming systems are usually complicated and difficult to learn.

Typically, PLs provide learning resources in the form of books and

documentation and possibly a perfunctory tutorial, and perhaps people

create a video series for it. This is kind of okay though—at least in

the case of professional programmers (or computer science students)

learning professional programming tools because it’s their job. But

everyone wants to learn to code these days, and I’m interesting in

creating tools that empower people (e.g.: journalists, scientists,

artists) to program computers without needing professional experience or

a formal computer science education. What if “learning to code” wasn’t

some ambitious side project you had to engage in through serious,

structured, dedicated study, but just the natural process of increasing

your competence in your existing tools? What if there was a way to teach

programming in a more engaging, gradual, and interactive fashion? Video

game designers have to teach players potentially very complex game

mechanics and keep them engaged while doing it. Can we take

inspiration from video game design in teaching people to use end-user

programming tools? Games that involve some

computational/automation features, such as Factorio and Minecraft, are

especially of interest here. Regarding Minecraft in particular, I am

interested in stealing the “ponder” feature of the Create mod for use

in end-user programming interfaces.

Barefoot programmers

In what might be a preference for provocation, I tend to tell people I want everyone to program—yes, everyone. Really I say this because I believe everyone deserves the chance to tailor their tools to their specific needs. Suppose everyone has unique preferences that could be catered to by a small amount of programming that extends existing tools (on the level of email filters, or little ad-hoc apps like Ink&Switch shows in Potluck). Still, not everyone wants to do the work of customizing their tools to themselves! They’d rather find someone else who made something adequate for them. For example, there’s nothing stopping you from buying your own materials to paint your house, and a lot of people do it, but also a lot of people hire professionals to do it. Perhaps a better example is something that doesn’t involve paid labor, like listening to someone else’s Spotify playlist instead of making your own. What would this look like in programming?

I want to take inspiration from modding communities of video games. Professional game developers create modding APIs or even fully-fledged software development kits for extending their creations. A few hundred or thousand hobbyist modders with professional or hobbyist programming and artistic experience then go create mods ranging from simple to very complex. And the broader community of gamers, which could be many tens or even hundreds of thousands, 1 use these mods that a subset of the community created.

See: there are layers to end-user programming. Much like the “barefoot doctors” from Maoist China 2 discussed in Ivan Illich’s book Tools For Conviviality, barefoot programmers could create a (free) marketplace for sharing customized extensions for any kind of software, but especially their local digital communities. In other words: journalists will make tools for other journalists; teachers for other teachers; dentists for dentists; and hyper-niche community needs can be met by situated software created by people in or around those communities, so long as for every hundred people there is one who is trained in very basic programming. Naturally, doing this well requires programming languages and systems which exhibit a far better learning/capability curve, which is the whole point of Illich’s book: the tools must leave the jealous hands of the professionals.

In fact we already see something like this with browser extensions! I

hesitate to lump in mobile app stores and GitHub, though, because the

former requires far too much knowledge and investment from app creators

(and is not based around extending existing tools, unless you count the

phone itself as the tool being extended) and the latter requires too

much knowledge and investment from app users. So, can existing

multi-layer communities of extensible software provide insights into the

plan for a democratic 3 computational

commons?

Taxonomy of Programming Tools

Following from Technical Dimensions of Programming Systems, creating a detailed taxonomy of programming systems is practically irresistible. I have seen diagrams charting different programming tools on various axes used rhetorically, but Jakubovic et al present the first attempt (that I am aware of) at a comprehensive analysis. The next natural question is: can taxonomies of programming tools form design guides?

Prior work emphasizes the differences in characteristics between systems; it seems to me that the most important practical concern—at least that which a sophisticated taxonomy can help with the most—is the interoperability between systems. In other words: it is less interesting how spreadsheets and Smalltalk differ, and more pertinent the limits of our ability to bridge those technical and conceptual gaps. I am particularly curious whether reifying the technical and conceptual dimensions of glue code (rather than sidelining it and trying to imagine new systems which are designed to be composable from the start) can provide practical affordances for composing programs. The argument being: if we let go of the myth that software used to be more composable, and we let go of the messianic prophecy of a future world where all systems are designed like Smalltalk, and instead we reify the world-as-it-is in our architectural models, we can use our existing techniques for managing abstraction to design more convivial systems.

Finally, while these attempts at a detailed technical taxonomy are certainly interesting, there is probably more good that can be done in the medium of a brief, persuasive essay or talk directed at a general software engineering audience. The goal is to shift professional perception of programming tools to better match the long-term vision of a world full of more situated and more composable tools for programming computers. Consider my words here as an example of the insufficiency of poor writing towards swaying opinion…

# The PL Way of Building

At HATRA, we ended the workshop by discussing some chosen topics in small groups. I ended up in a group talking about how to systematize tacit PL design knowledge.

What is tacit PL design knowledge?

A premise I’ve heard many times: PL has knowledge to offer other areas of computer science, and other fields entirely. This is not some fringe opinion. Armando, in his Robin Milner Award acceptance address, said that PL can be thought of as a solution oriented field where we develop techniques and then find problems to leverage them towards (like ML and theory do). Formal verification in hardware and security are great examples of this. I’ve also heard that we can help the databases community with their problems…

It’s kind of an arrogant thing to say. Wasn’t the lesson of category theory that various branches of the same field tend to invent their own language and notation for the same underlying ideas? Wouldn’t the area of computer science which is most in love with category theory understand this? Or is that exactly the point: we know other fields have come up with similar insights, and we are trying to unify our language so we can understand each other and collaborate better?

To start off the discussion, we attempted to rattle off some of the things that comprise this tacit PL design knowledge—those things we value as a research community and which may generalize to other fields:

- orthogonality

- compositionality

- reusable abstractions

- local reasoning

- correctness

- formal reasoning

- separation of concerns (i.e. modularity)

- canonicity/simplicity

- intuition for designing sound type systems

We concluded that the “PL approach to solving problems” was the critical thing, and it consists of a systematic, theory-oriented approach, where instead of just blowing away the problem all in one, we develop tools and techniques bit by bit, chipping away at the problem until it becomes trivialized. We achieve this through proofs and formalism.

Though I think these particular values are rather specific to the “types and formalism” side of PL, this side is also the one which seems to be most eager to spread the gospel of PL with the rest of the world, so let’s proceed…

Success stories

I asked the group whether they could think of any success stories. We came up with two:

- using types in networks to verify router protocols

- the UI component model in web programming

Surely there must be more!

Considerations

While composability is one of the PL community’s favorite buzzwords, enjoying proverbial applause whenever mentioned, we admitted it is not always a net good. Composability (and immutability) are often in tension with other desirable properties, like easy-to-follow procedural code, concreteness (over indirection), and minimal overhead to ensure performance. In general, if you imagine as a developer you have only a finite number of tokens to allocate to a piece of software, would you rather spend them building beautiful, complex, reusable abstractions, or on practical methods, useful libraries, and documentation? If you think the former, you may find yourself at home in the PL type theory and proof assistants community…

In summary: even after a genuine attempt to tease out the value of PL when applied to other fields, I am unconvinced there is anything concrete to contribute. Perhaps I just don’t know the real success stories. Further research is needed.

# Taking an interest

Last section on academic research, I promise! You must understand I have been getting very immersed in this stuff lately, and SPLASH is like getting poked by white hot metal, if academic euphoria generates heat. The weird thing about it is I’m not taking any classes, so that academic euphoria, to extend the metaphor, has a restricted spectrogram. I get to have the high-level conversations at lunch with my peers, but I don’t do the day-to-day “real work” of learning and researching that lends it meaning. It’s a terrible feeling to come up with an exciting idea and then not go try to implement it, or to see a talk and then not continue studying the topic more deeply. Software engineering has the advantage here, since a big part of my job is to come up with ideas about how to fix problems or improve our product, and then go do it.

The result of having pretty much exclusively high-level discussions about research is I’ve done a lot of soul-searching about why I am pursuing an academic career and what I hope to achieve by doing computer science research. Since I’m not in the academy right now (but just on the periphery of it), this ends up centering not around down-to-earth technical ideas and research methods, but the value one adds to society by doing one kind of research or another.

I chatted with Dylan about the importance of marketing your research to broader and broader audiences, not just for getting grants but because it’s good to take an interest in your work and your field. We live in a capitalist society which means, among other things, that the primary way you relate to society—and the primary way in which your worth is evaluated—is through your labor, so you might as well dignify it. This is especially true if you have such a relatively cushy and empowering job as software engineering or “professing” in which professional conferences are a big deal and the third-favorite way of harming the environment (after using LLMs and living in a first-world country).

Here’s what it maybe looks like to think through this:

- I am researching type-directed synthesis of pure functional programs with typed holes.

- Because program synthesis helps programmers generate correct code from specifications, but programmers are reluctant to write specifications, so we focus on completing incomplete programs, and pure functional programs are better suited to existing synthesis techniques.

- Because programmers tend to write buggy code, and synthesis helps write code that is correct (at least type-checks) on the first go.

- Because I want software to be more correct.

- Because downstream of correctness, on the user-facing side, programs are more reliable, and on the engineering side, less work is required to maintain and debug them.

- Because software user interfaces are not as good as they could be

This is, as far as things go, actually fairly compelling and straightforward to my naive eye. It gets a lot more suspect when you’re working on something that has been tried and failed before, as is the case for all the people I’ve met this week who fervently believe we erred in the last century when we didn’t start writing all software (at least user applications) in Smalltalk. The existential fear there is that poor programming practices and system designs are so deeply entrenched in an immovable industry that we will never get rid of the current, underwhelming software stack. For program synthesis, the existential fear is that generative AI makes the entire subfield obsolete.

Most researchers I’ve met seem to think about their work in this way: there is the specific research they’re doing, which contributes in a small but significant way to a larger research community, who have a shared motivation to improve the status quo along some axis corresponding to a higher-level social or technical goal aligned with their personal and professional values, which is subject to scrutiny and skepticism from within and without because the worst thing you can do as a researcher, next to committing scientific fraud, is spend a lot of effort working on something that doesn’t matter or doesn’t last.

Once you notice the pattern, the discussions about the significance of your work become pretty depressing. Worrying about whether your work matters is not specific to research, let alone programming languages research in particular, but research uniquely organizes itself structurally and culturally around the explicit goal of creating lasting artifacts that contribute to an overarching goal, and failing to do this is failing to be a good researcher. And, by extension: failing to be a good member of society, since your worth to the world is your worth in your work. Even if we admit that failing to obtain positive results is not really failing as long as you do good work (though scientific institutions are very bad at creating structures that support this), we would still be left with a profession in which activities instrumental to this overall goal are horribly disincentivized.

Consider some cherry-picked cases where important activities other than generating lasting, impactful artifacts is acknowledged as important, even if not well-incentivized:

Teachers teach the same material to new students every year, with gradual modifications year by year as curricula and students’ needs evolve. They rehearse lectures and recite them; they assign assignments and grade homework and papers which contain the same distribution of responses every year. Aside from innovations they might make in their pedagogy, there is nothing novel about what they are doing. They contribute to society by sharing their knowledge in structured ways. They perform a service.

Programmers, we like to think, create software which lasts a long time and other people use, like a novelist writing a novel that goes into publication, and then they go write more software. But this is not actually true most of the time. Programmers less often write programs, and more often read and debug them. If you squint at the software industry, it really looks like computer scientists invented this horribly fussy thing called a computer which runs even more horribly fussy things like programs which form complicated systems that society depends on, and programmers exist to manage the onerous task of keeping these complicated systems running as they break and as their requirements evolve, and, sometimes, if it hasn’t been done already, they transform analog bureaucratic systems into software (such as civil society becoming social media, taxis becoming ride-sharing apps, and any number of niche services becoming generative AI). There’s an arbitrariness behind it all—“why don’t the systems just work by themselves? Why all this tedium?”—that has more in common with than it does with plumbers than it does with artists or designers or even other engineers. Programmers perform a service.

The menswear guy on Twitter contributes to society by knowing a lot about fashion, and using this knowledge to quote-tweet posts containing poor use of fashion with long, detailed threads breaking down and repeatedly arguing why fashion is meaningful and interesting and how it is one of the most significant ways in which we establish and communicate social relations. When he started, his “thing” was pretty novel, but at this point he has established his form and yet persists, dutifully, even though he sort of sounds like a broken record in some cases now. He probably could just reference old threads to cover almost every case now, but social media like Twitter is better when it is an active conversation, even if that conversation involves a recapitulation of old ideas. Menswear guy exists in a context—a community—and his work is publicly accessible. He is, in his own way, an educator. He performs a service.

So that’s my thesis: try to conceptualize your work not in terms of legacy (artifacts entering an archive, with humans accessing and using that knowledge as an afterthought), but rather as service. As a computer science researcher, perhaps your primary purpose is to develop convictions about how something can be improved, gather evidence to back up your claims, and then spend inordinate time and effort going to conferences, giving talks, and writing papers and essays in order to convince your community you are right—and if you do not succeed in doing that, you are still contributing to society by trying, since there’s always a chance you were actually wrong the entire time and your ideas shouldn’t be accepted.

As an effect of this reframing, your worth is defined not just by your output, and but primarily by your continued presence and performance. It is more about your inherent worth as a person who exists in a place and time, in relation to other people, forming a community or institution.

# Edification

I’ve been trying to read more, because I only have 11 months left to live (before I go to grad school and become reborn again as a PhD student). To this end, I finished Dune finally (it only took me 10 years) and I also read Elif Batuman’s two recent novels, The Idiot and Either/Or. I have nothing to say about this book that won’t be extremely embarrassing. Prince Charming…

The Idiot and Either/Or

This is not a book review, despite whatever ungenerous thing is written at the top of the page. “Book review” sounds so impersonal and critical. My experience reading about Selin’s first two years at college was deeply personal; I found Selin’s relationship with books reflecting back at me, commenting metatextually on how I read her story. Especially in the second volume, Selin begins to think she is going insane as each book she opens appears to have something uncannily pertinent to say about what is going on in her life 4.

The more I read, the more parallels I found to my own experience. The emails Ivan and I had exchanged, which had felt like something new we had invented, now seemed to have been following some kind of playbook.

A poem in Real Change titled, increasibly, “And to think, she’d never been kissed.” Was I losing my mind?

All of these coincidences are made more extraordinary in the light of a literature class she attends called Chance, which elevates contingency to “the royal road to the unconscious.” Even the books she reads appear to come to her providentially, bearing circumstances and content replete with meaning. I wrote in the margins, “I recognize pattern and echoes in Selin recognizing patterns and echoes.” She had the burden of needing to comb through thousands of pages, of texts classical and prosaic, in order to find the nuggets of wisdom relevant to her situation; I had the fortune of finding it all in one convenient bildungsroman.

Of course this is not true. As Selin realizes, the books she reads don’t give her the answers she is looking for 5. Frustrated by the limits of literary knowledge, she finds her narrative apotheosis by abruptly rejecting established narrative, in a conclusion I found reminiscent of the end of Fleabag. Can you imagine how that feels to read? It’s like the novel finishes with Selin jumping up from the page and, boasting her venerably long Goodreads, sagely informing me that knowledge does not come from books, and actually I need to stop comparing myself to characters in novels, and go live my own life. How dare she! What about my great plan to read all these books really fast?

Fortunately, I didn’t intend to find the answers to life’s questions by reading books. Batuman’s first novel just grabbed me the second I started to read it, at a time I really needed a distraction, and then Selin’s narrative gradually possessed me the same way she is possessed by the narratives she attaches herself to at Harvard. Too bad I’m not spending the summer in Hungary or Türkiye. It seems like it really helped. Anyway, in real life Batuman proceeded, after graduating from Harvard, to go straight to graduate school where she—you guessed it—read more books. A lot more books. Everyone who is very intelligent tells me you can’t learn how to live from books alone, but they also read several magnitudes more books than I have, even at the same age as me. Maybe books tell you how to learn from sources other than books. I’m not sure—and there’s only one way to find out.

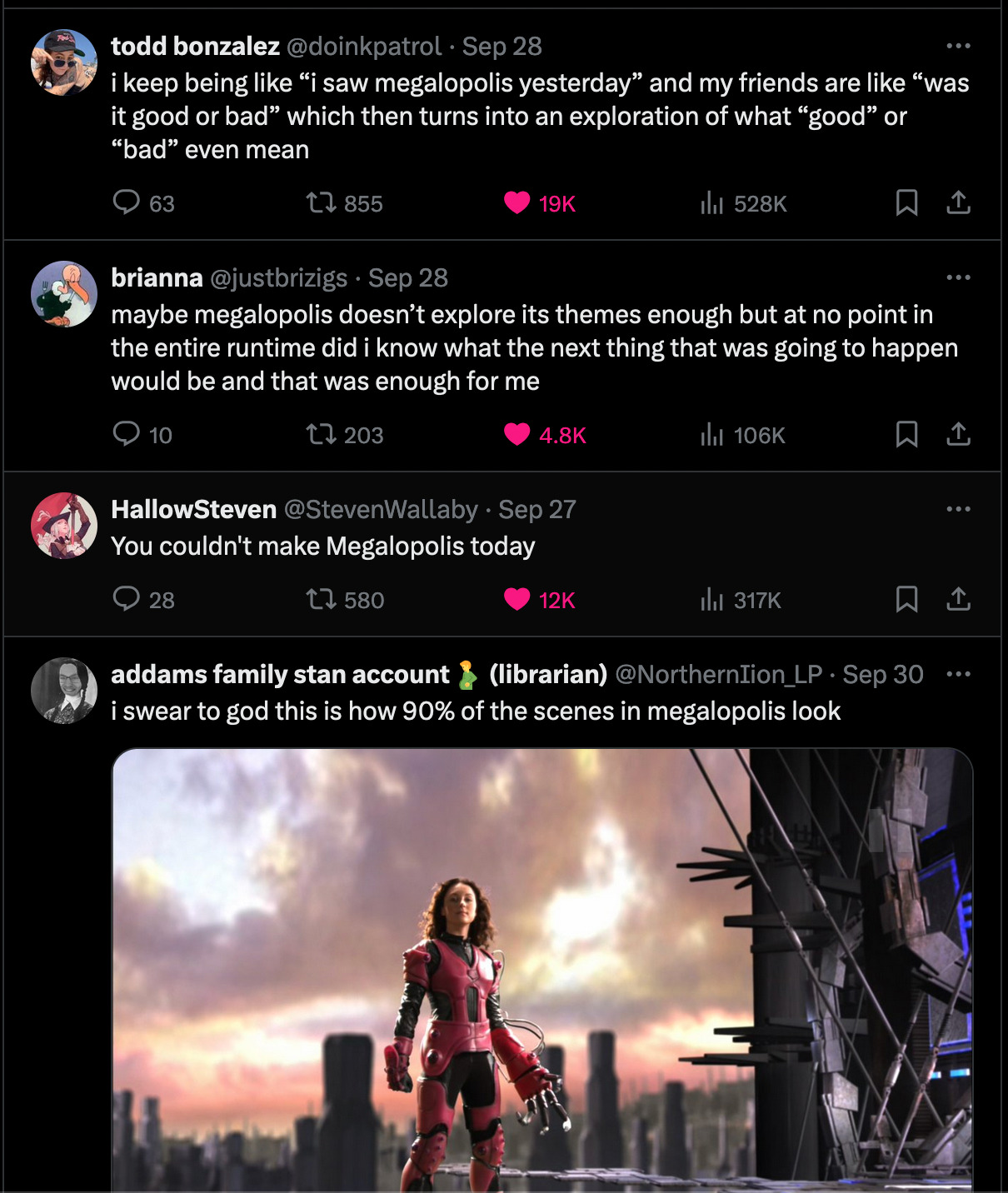

Megalopolis

How about movies? Have you seen Megalopolis? People seem to be regarding it as a triumph, but I think it’s more like a pyrrhic victory. Yes, it’s a terrifically imaginative and hilarious fever dream of a film that will hopefully influence mainstream and arthouse cinema alike forever on… but at what cost?

Anyway, look at these funny tweets:

Dune

I also watched Dune (2021). Uhhh people raved about it for so long and I built up these great expectations in my mind. Except, having read the book, I found it slightly disappointing. Don’t get me wrong: it’s a very good movie… but it’s not a good adaptation of Dune, the book, and yet I seem to recall everyone suggesting it was the only faithful adaptation yet committed to screen. The whole point of adapting Dune, the whole reason it has this legendary status as impossibly difficult to adapt, is that Herbert does masterful things with the specific medium of the novel—at a very basic level, many of the most compelling scenes center around battles of the wits being fought in the minds of people speaking to each other, given form in the close-third prose and by writing down characters’ literal thoughts. I was grateful that Villeneuve didn’t reach for voice-over to adapt this, but he rather ignored it entirely, and cut out all of the scenes which hinged on it. Just look, for example, at the meeting of Jessica and Shadout Mapes. For me, the most interesting parts of Dune (the book) were those about the Missionaria Protectiva, and I also lovingly recall the dinner scene in the first part, which was entirely omitted from the film. I begrudgingly admit that the dinner scene was a good omission under the constraints of a feature film, but it still makes me a little sad.

Dune (2021) ends up being a pretty good—maybe even great—epic scifi-fantasy film… but it is not a faithful adaptation. I think that the problem isn’t Villeneuve’s ability or some inherent inadaptability of the novel, but the limitations imposed by the tyrannical hegemony of the feature film. In an age where we enjoy indulgent streaming-exclusive television miniseries, why would you choose to mutilate the story to fit the format of mainstream cinema? I am vindicated, once again, of the genius of Dinotopia.

So Dune (2021) wasn’t that good. But I keep loading it back up and watching scenes from it, because it just feels so good to watch. How does that make any sense?

# What else ought there be?

Some other things that have crossed my path lately:

- David Byrne’s obsession with buildings and physical infrastructure.

- Who is supposed to benefit from advancements in human-computer interaction? Is it programmers? Scientists? Artists? Journalists? Teachers? Children? Everyone? No one?

- Interstitial social media—the places you pass by on your way, rather than overtly attractive destinations to stop and languish.

- Theurgy.

- Frustration with Emacs. Seriously: does anyone know why it takes so long to save a file? It’s really wearing me down.

- Are you in love?

That’s all for now!

With good tidings,

cs

Or millions in the case of Skyrim and Minecraft…↩︎

I was told I shouldn’t mention Mao in my research proposals. In fact, I don’t need to, since the barefoot doctor program actually began before Mao, in the Rural Reconstruction Movement (it was taken up in earnest by Mao). But I like to cite my sources faithfully, and Illich does discuss Mao. Also, it bothers me that, in computer science, there’s this huge taboo around discussing science the spectre of communism. It’s as if my colleagues are worshipping the wrong McCarthy…↩︎

More like anarchical, actually… Websites hosting mods and browser extensions do have social voting systems, but I don’t get the vibes of an organized democracy from those places.↩︎

One of the really funny recurring bits in the novel, as a result of Selin’s incessant pattern-matching, is that every third paragraph or so ends with her connecting an observation back to Ivan. For instance, after seeing a documentary about black holes in science class, she decides Ivan is the void at the center of her universe, his absence keeping “all the elements whirling around me … held in place.” The frequency of such ruminations borders on irritating (and sometimes crosses over), but I found it so charmingly amusing—Batuman obviously intended it to have this effect, so I was not annoyed at her but at the narrator, which made for a compelling experience of basically shouting at the page for her to get over him.↩︎

I feel dishonest to say that Selin doesn’t get any wisdom from books. In fact, Breton and the other things she reads are remarkably important… but not on their own. It’s true that what they have to offer only becomes crystallized through intentional action. Far from merely reading the text and becoming enlightened, like Augustine in the garden, Selin learns her lesson only when the words bounce around in her mind for months, through a whole Turkish adventure, and still then only when she decides to do something with it. Now I’ve been unfair to Augustine: he, too, only earned his revelation after years of trying. The encounter in the garden was not the singular moment, but the culmination of thousands of moments.↩︎