Pretending & Pretension

Jun 27, 2024Table of Contents

# Modern Art: Anyone Can Paint

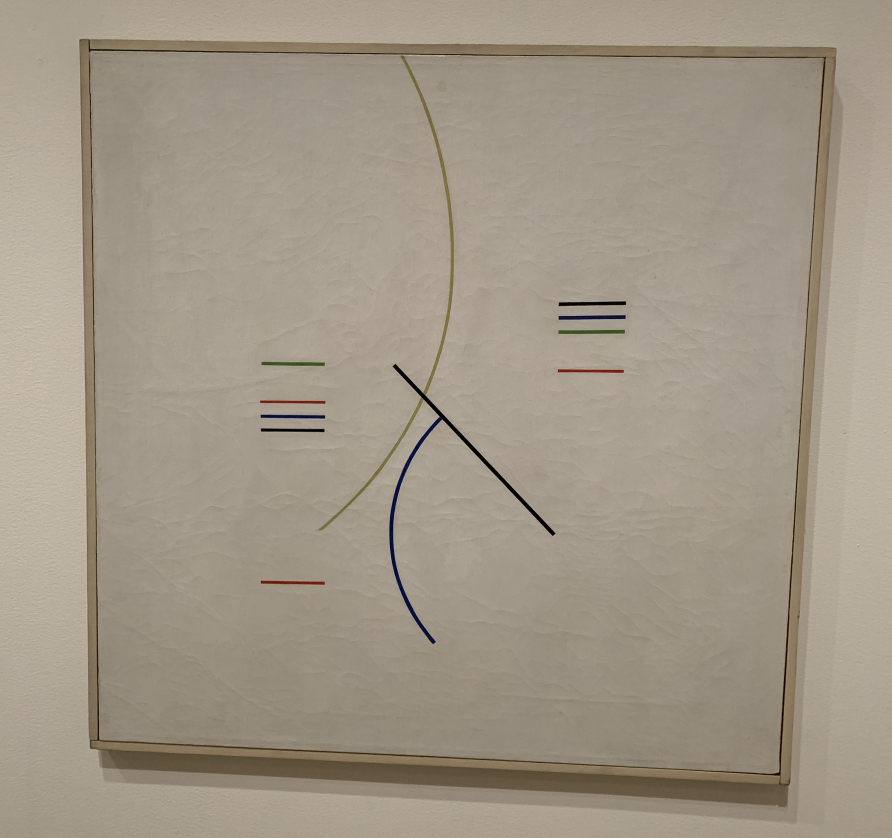

During a recent visit to MoMA I saw this 1948 piece by Alfredo Hlito:

This painting to me evokes balance. The strokes have a satisfying precision to them, as if made by machine, yet unmistakeably the work of hand. The canvas is a bit crinkled, as if worn—I’m not quite sure if this is a sign of age or if it is a property of the material.

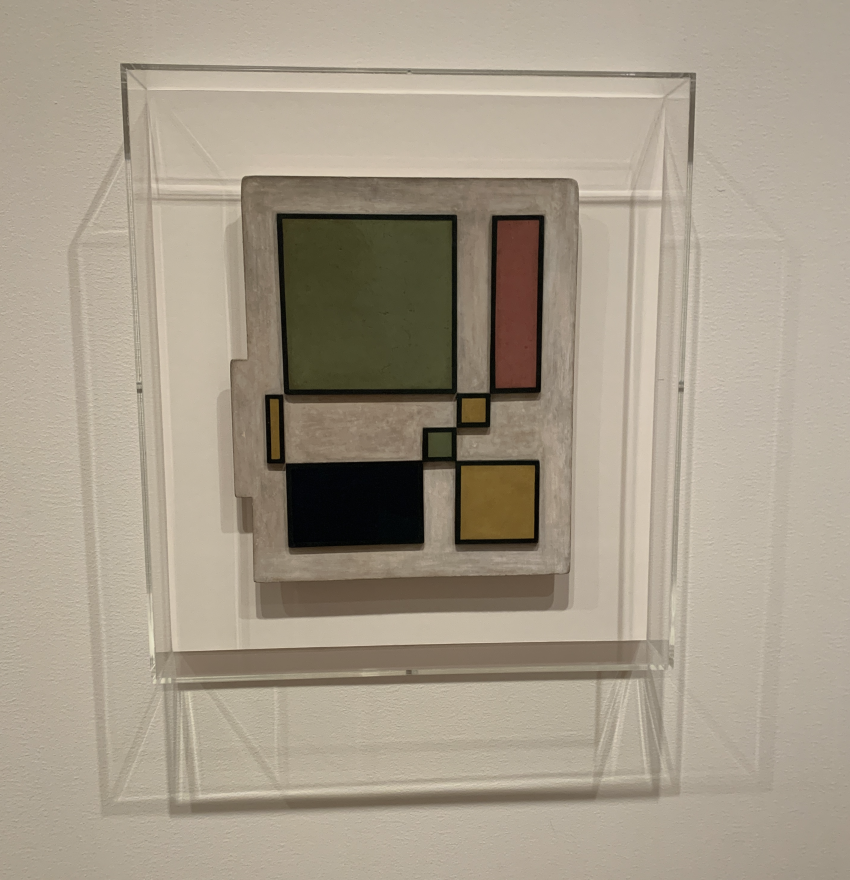

Then, a young girl—maybe 6 or 7—came by holding a smartphone and started taking photos of Hlito’s painting and the other modern art pieces around it. “I could draw that,” she exclaimed, looking at Rothfuss’s Yellow Quadrangle, and her father trailing behind said, “I think you could draw that too.” This is the painting she was looking at:

Once she got her photo, her father rushed her along—“come on, let’s go.” The self-assured journeyman art historian in me regrets that the girl blew through the gallery room in under ten seconds; if she stayed longer, maybe I’d have made up my mind to capitalize on the teachable moment. I could say, “first of all, it’s a painting, not a drawing, so you couldn’t draw that—maybe you could paint that.” No, what a terrible snide thing to say!

I would begin not by correcting but by expanding her understanding of the piece: “it’s not just a drawing; do you see that it is 3D?” Thus revealing what basic details you can appreciate when you take a little more time looking, and use your body instead of your monocular camera lens to view the work.

Yellow Quadrangle has balance like Hlito’s piece, but weightier and easier to dissect. The weight comes from the large colored blocks, of course, and from the material: a thick board cut and painted such that the blocks are outset. Where Hlito created a painting, flat and unassuming, Rothfuss created an object with mass, scale, and texture. Both could be hung in a rich household’s living room. These remarks are obvious. A child could tell you that. I like to imagine that, if asked to comment on her observations, this girl I saw would notice the same things as me. That, I think, is what distinguishes Rothfuss (and Mondrian, and others from this school): their art is for everyone. They are completely unsubtle. Everyone can appreciate what makes Yellow Quadrangle good. The formal elements of the composition shout at you, “this is who I am! this is what I’m doing!” The art itself is didactic.

This takes a lot of effort, I imagine. Usually, when someone remarks, “I could draw that,” with regard to a Mondrian or a Pollock, it is intended as a negative judgment on the piece and on modern art as a whole. Art should be difficult to create, they think. It should take skill. Doesn’t Yellow Quadrangle take skill? I presume there is a lot of trial and error and design sense (that intuition which only comes from experience) behind the careful composition. The blocks are unbalanced, but arranged as they are, though precarious, they attain balance. They evoke a house of cards, or a jenga tower: right now a local minimum, a low-energy stable configuration, the next moment knocked into chaos by a small perturbation. Yet it feels calming and orderly. So perfect, it could never fall apart.

That sounds difficult to compose from scratch. But, wonderfully, it’s very easy to copy. Any kid can take a piece of paper and some colored pencils or crayons and render their own copy of Yellow Quadrangle without much fuss. They would get very close to a perfect flat projection of Rothfuss’s piece, modulo the precise colors and texture. The more experience you have and the more tools at your disposal, the sharper your lines, the closer you get to an exact copy—never quite perfect but good enough to make you feel you participated, you were able to create something. And once you see the pattern (the sense of balance is inherent, deeply ingrained in our brains) you too can go through the process of trial and error to create your own unique composition without any special skills required beyond the ability to draw a straight line and color in shapes. I think this is why people say, “I could draw that!” to Mondrian and Rothfuss, or to Pollock’s splatter canvases. They mean it. They’re right. They can draw it. So why is it said as if intended to be a putdown?

I bet the girl heard similar remarks and echoed them in that parrot habit kids have. She was trying out how it feels to utter the common refrain against modern art. In my experience saying that sort of thing (all of us have done it) it feels hollow, like I have not gotten to the bottom of what’s going on, and I’ve settled for a lazy dismissal instead of pursuing understanding or cultivating appreciation. I hope it felt hollow for her to say it, too, and I hope she elects at some point to make more of an effort to see what’s in front of her. That being said, I empathize with those who say it seriously. I understand having this reaction to an art world that emphasizes obscurity and admits only interpretations available to those with a wealth of knowledge of art history. That’s exactly why I find non-representational art (and related movements) so exciting: they are essentially a rejection of this elitist, exclusionary trend within the art industry and the stuffiness of private ownership. Abstract art is great to have in museums because it is, in a way, the epitomic “art for the people.”

Or perhaps nothing need be taught, perhaps there is nothing to be fixed. The little girl’s exclamation, “I could draw that!” was not a critique. Children are honest about how the world around them makes them feel. We can interpret her differently. She was saying how excited this piece made her, how it told her she could be an artist too, how it was relatable, how she could imagine herself creating it. That intuitive reaction is far more valuable than any pretentious lecture on modern art. Unlike most artists and critics, she engaged directly with the work and announced her reaction to it. That is priceless.

# Observations

Comfort is no comfort to me anymore. Instead I seek experiences to add to my collection.

There is astonishing beauty everywhere I go—even the ugly places. The light which lends the world its colors moves too quickly; it resists my pleas to stay put and my prayers that every moment would last a century.

I am best at sitting still when everything around is in motion. Those who seek to capture the world must be great observers, recording each moment, dutifully reshelving life into fiction. They write a story, or click a shutter, or jot a poem, and each capture is an nonequivalent exchange transferring the outer world into their inner. If not theft, it is informational piracy.

Such a person is not of the world. Where do they live?

Do they stand above us looking down, taking remarkable fragments up to a higher shelf like a messenger whispering in the ears of a greater power? Does their attention dignify us?

Or do they stand among us, aloof, pretending at artistry while in fact no wiser or fuller than those of us who live in the world?

A hundred moments captured, a thousand noted, a million moments slip me by. A moment captured, I’ve found, festers rotten unused. Ripped from its context, experienced flat instead of full, memory fading; this is no way to treat a slice of life. Make something your own of it, urgently, or let it go free.

# Parlor

David Bieber of Google hosted a hack session at Betaworks. Omar and Andrés were there. A founder called Michael Fischer was there. And I was there. Michael came up to me and introduced himself and we spoke about his startup, waterbear.science, a blockchain for scientific datasets designed to reward scientists for publishing their data and for using open data to generate insights. Aside from my default aversion to blockchain (really a reaction to recent years’ cryptocurrency overhype), it seems rather neat. But a startup? Why must everything be profitable? Do we not profit from apparently useless activities, personal experiments guided not by feasibility but by curiosity? Another attendee at David’s event, whose name tragically escapes me, related to us her personal project on organizing all her notes from autodidactically exploring the 17th century… and discovering blind spots in her research using a custom tensorflow model trained on Wikipedia links. The latter part of the project sounded less like a robust technical solution to a serious problem and more like an elaboration of the question, “I wonder if this is possible…?” I have abundant respect for this sensibility.

# Homework

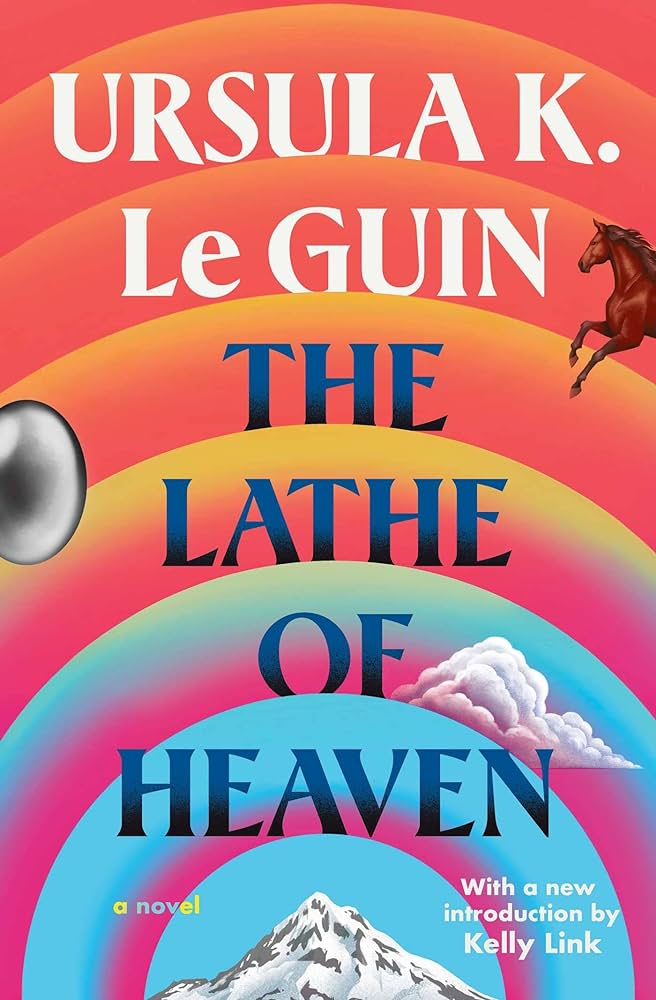

I opened up The Lathe of Heaven 1 for the second time. The first time I opened it in Prospect, leaning against a tree on an early warm day of spring. A serendipitous Tweet from Andrew Blinn let me know it was divinely ordained that I read it. Kelly Linker’s preface compelled me forwards, and the jellyfish stopped me in my tracks. I put it off for later.

‘at least we kept out the casuals’ whispered entire genres of software as they were ground to dust on the lathe of heaven

Later has arrived. At Eden’s recommendation, I continued past the first page and found something remarkable. In Lathe, Le Guin deftly develops the mechanics of a sci-fi concept, called “effective dreaming,” through a series of therapy sessions featuring the central characters. But so far, halfway through the book, I am most impressed how Le Guin employs shifting the close third perspective from character to character to further the plot and the reader’s understanding of the central “technology” of effective dreaming. I cannot help but read Le Guin’s books with an eye towards the craft of writing. Here, I find it instructive to imagine removing some formal element. If Le Guin omitted the changing perspective and focused entirely on the interiority of George Orr, the book might benefit from the added ambiguity about the reliability of his account, but we would lose a much more interesting aspect of the concept: the bystander’s perspective of his dreams. Though initially surprised that she clears the ambiguity so quickly, I now appreciate the choice to focus on each character’s experience of effective dreaming.

Once I finish the book I expect I will have something to say about the details of the futuristic Portland outlined by Le Guin. I found myself ready to levy critique against her naive vision of post-automobile globally-warmed North America, but when George dreamed of the Plague Years, I realized there was not just one future described in Lathe, but many conflicting futures. An analysis of her world-building becomes correspondingly more complex.

My own fault—it slipped my mind—I did not invite Eden to annotate the book before she returned it to me. I’ll get another chance with the Bhagavad Gita 2 if I borrow her copy. Do you know this? That you must ask your friends to annotate the books you lend them? Then reading becomes a delayed conversation. Shira was kind enough to carefully annotate Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow 3 for me. It is just as lovely to receive a copy annotated as it is to receive one annotated for you. The difference is the intention: am I annotating for myself (and you happen to read it after me), or for you? Both ways enable the intimacy of reading together separately.

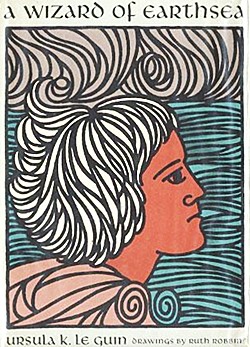

I also re-read A Wizard of Earthsea 4. It is rare that I allow myself to read in the way I did: opening specific chapters and reading portions, jumping around, reminding myself, following curiosity rather than linear page progression. I now believe this is a wonderful way to re-read. Once you know the scope of a book, you can return to it like an old friend, and jump around to bits and pieces you remember, reading just as much as you please, discovering new connections and allowing yourself to revel in the prose.

If I recall correctly, I came to re-read A Wizard of Earthsea because I wanted to share a passage out loud. This, too, is one of the unique intimacies afforded by sharing a book with others. It is just as well to send a picture of some compelling passage over the internet… though I do take pleasure in reading aloud.

I have been slowly flipping through Lost In Thought 5 by Zena Hitz every time I have a spare moment. It has served a consistent function for me: a frequent reminder that my most tightly-held and important mission is learning. This takeaway is compounded by the fact that I’m reading this treatise on the dignity of everyday intellectual inquiry while riding the subway, waiting in line, or, indeed, sitting on the toilet. Now that I’ve finished it, I have a broader perspective on Hitz’s overall argument and I can take issue with this concluding argument:

Scholarship is exciting in its own right, but it means nothing in a world where there is no first-order reflection, no ordinary thinking about human nature or the structure and origins of the world. Higher study is pointless if literature or philosophy or mathematics or the nature of nature has ultimately nothing to do with the human good of ordinary people or with paths of understanding one might follow in daily life.

I’m not convinced that Hitz is correct here! Her central assumption seems to be that the topics of study in intellectual institutions should be mere elaborations of matters accessible to the layman pondering the cosmos on his daily walk. Or that it should be possible to trace every activity in the university to a purpose that somehow benefits the everday intellectual. While noble to imagine every academic question participates in the grand quest for universal human truths, I am not sure that is a good idea. Certainly, intellectual institutions often invent their own reasons to exist, but they also often do work that is simply difficult to justify from basic principles because it is so technical. Specialized division of labor (in this case, intellectual labor) allows us to create and use technology (in this case, advanced and niche research techniques) that simply would not be possible in the good old days of Plato’s Academy. This is a good thing because it means we can answer important technical questions without getting bogged down in the need to tie our work to the universal questions of the human condition. Sometimes we really just want to know how to assign processor registers efficiently in a compiler, and so we invent tons of niche jargon and obscure techniques just for this purpose. That this bolsters other research and development is a good enough reason for it to be studied.

But Hitz’s argument is largely a defense of the humanities; my point holds for the humanities, too! It is totally appropriate, I think, for a scholar concerned with the details of post-Marxist philosophers’ uptake of Hegelian dialectics to use jargon that is neither known nor relevant to the everyday intellectual. Even if, after a thorough audit of such an endeavor, all we can come up with for a reason to exist is better understanding of the origin of dialectics as invoked today, intellectual inquiry retains the dignity about which Hitz is so concerned.

For a book that seems to be one big complaint about grant-writing, its conclusion seems to be little more than a suggestion for how to pick academic research topics that sound good on grant applications. Perhaps that is unfair. In fact, I felt this was tangential to her actual gripes with academia. In an earlier passage also in the final chapter, Hitz reveals the real frustration that motivated her to write this book:

Not long ago, I came across a hundred-year-old scholarly edition of the Annals of Sennacherib… The introduction broached the human question most evidently raised by the work—the corrupting force of absolute military and political power:

History begins with the vanity of kings. (Will it end with the vanity of the demos?)

Scholars today are both too sophisticated and too diffident to appeal to such an obvious, profound, and universal question in a work meant for specialists. They hide the human under jargon, or lose sight of it altogether.

Firstly, I believe you can write this way. If it sparks joy in you, it probably sparks joy in Reviewer #2 (who is, lest we forget, a colleague and also an academic!). Secondly, this quote, too, is technical jargon! It just happens to be relevant to scholars of ancient political philosophy… such as Zena Hitz. Perhaps this is why she focuses so intently on “universal questions” of humanity: they are the subject of her particular field of study. Other fields, like programming languages or Hegelian dialectics, may be able to employ rhetoric to argue for their grand importance but ultimately must contend with their relatively narrow domain—especially when your research programme deals with the technical details rather than the mass appeal, which is usually the case in academia, by design.

So, I interpret the book differently. Rather than suggesting “higher study is pointless if [it has] nothing to do with […] ordinary people or […] daily life,” Hitz, by her own example, implores us to uncomprisingly defend the value of our intellectual work and to rely on the virtue of seriousness as a source of dignity and communion in an otherwise humiliating and fragmented world of false needs.

# Questions

Is it evil to neglect the use of your skills?

Some find it meaningful to commit to a life of selfless service to others; is service a vanity, a vice, or a virtue?

What is the purpose of intellect: to simplify, or to manage complexity?

What else ought there be?

Good tidings,

Carmel

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Lathe of Heaven. Simon & Schuster, 2023.↩︎

The Bhagavad Gita. Translated by Eknath Easwaran, Vintage Books, 2000.↩︎

Zevin, Gabrielle. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. Knopf, 2022.↩︎

Le Guin, Ursula K. A Wizard of Earthsea. Clarion Books, 2012.↩︎

Hitz, Zena. Lost in Thought: The Hidden Pleasures of an Intellectual Life. Princeton University Press, 2020.↩︎