Structure & Whim

Profferring a new dichotomy July 5, 2025

I’ve been confused, or as E likes to call it, indecisive. For the better part of six months I have been slowly gathering ideas, fragments of a theme. One day I was permitted to see the coda, and I had a free afternoon, so I found my way to decision and I sat down to write…

Following the trend of the titles of these essays/reports/dispatches, here I present yet another conjunction—in this case, a dichotomy. Structure and whim. Structure versus whim. I do declare: it shows up everywhere!

# Computational structure and expressivity

I quit my job and took a 5-day trip to visit the love of my life: New York City. There, between visiting old friends and making new ones, I attended Omar and Cristóbal’s Screenshot Conf.

Of the many talks that took my breath away, one was on bitmap-first text editing. A revelation! Of course! Of course! The digital notebook is a surface for drawing, not a sequence of ASCII characters! It should be an image!

The merit of plain text is its flexibility. The downside of plain text is its lack of flexibility. Plain text is an elegantly simple structure. A text file is just a sequence of bytes with a certain width that are interpreted as letters. Letters, these discrete, unique objects, are the foundation of plain text’s delicious harmony between the linguistic composition of words and their formal structure in the computer. The engineering tradeoffs of such a basic format prioritize the gains of simplicity (easy implementation, universality) over the gains of complexity (structure amenable to computation, potentially greater expressivity) because the costs of complexity (strong assumptions about the object and its uses), and, at a deeper level, clash with the raison d’être of plain text in the first place. Plain text is basic, must be basic…

Best understood in contrast to rich text and even richer things than that, plain text doesn’t offer any notion of document structure or multimedia or spatial relations or font or color or interactivity, because all of these features—while expanding the possibilities of the proper use of the format to include richer interpretations of what “text” might be—constrain the flexibility of its ontology and shave away the creative potential for abusing it.

It’s exactly that flexibility of ontology implied by the simplicity of the structure that gives us nice things like HTML, which does support multimedia… albeit mediated through the concept of a browser to fetch resources and a web server to provide them. In that sense the complexity is still there, just shoved to the side…

Low flexibility in format produces high flexibility in application, at the cost of expressivity… where by expressivity I mean provisioning a high-level user-facing language, situated in the specific application context, for interacting with the system.

In the case of digital notebooks, plain text is not enough because notebooks are inherently spatial. When writing notes on the computer I use tools that parse Markdown so I can get the expressivity of document structure and compute on the text to produce multimedia output, but still, including things like images and asides is a pain… Introducing bitmaps… All the visual, spatial elements of notebooks, and none of the linguistic structure…

Of course you can build hackish algorithms for computing with text-like bitmaps, in both directions (use the keyboard to type letters and they will appear as pixels, then detect pixels arranged in the pattern of text and convert them to ASCII for processing…). And this is basically similar in spirit to what we’ve done with plain text, building entire computer systems on the standard via parsing. The fact that this is possible is a testament to plain text’s ontological flexibility; the fact that it’s so easy to make mistakes writing “strcutured” text (e.g. Python programs) is a testament to its poor expressivity.

Since there are two kinds of flexibility here, we should give them nice names. Let “flexibility” refer to flexibility in format (i.e. flexibility of structure). As for flexibility in application (i.e. flexibility of ontology), call it “whim.”

Complex structures, since they encode brittle notions of application, limit whim. Simple structures encourage whim.

Both bitmap and plain text have rigid, simple structures and permit whim.

# The dialectic of productivity

Whim is sort of like freedom. But the relationship between structure and whim is not so straightforward in all cases. It’s especially ambiguous in the case of a conversation you may here between any two people. It goes like this.

The One: “I like having a 9-5 job. I need that structure in order to be productive.”

The Other: “I appreciate flexible hours, because too much structure makes me anxious and less productive.”

The fact that is varies, validly, from person to person implies there is no universal answer, that the relationship between structure, whim, and productivity is a matter personal self-knowledge. And it’s not even so simple as preferring one or the other, or a spectrum… What time of day should be structured and what should be left to whim? What days of the week? What part of the year? What tasks, what responsibilities? Does it depend on mood, or energy, or enthusiasm? Solitary versus collaborative activities?

The Other might argue that structure makes a person complacent and deadens creative thought. But David Lynch ate the same thing for lunch every day, claiming that the routine removed a variable—what to eat—that would otherwise take up space in his working memory that could be allocated to creativity, i.e. letting the mind and spirit soar to whimsical heights…

Under conditions of absolute freedom, do we lose ourselves, tire, and enter a mode of ignorance and passivity? Or do we seize the pure potential and sustain a state of pure active direction?

Hobbies

Never make your hobbies your job—because that enforces structure on what should be whimsical.

Consumerism

Before we go on, let me disclaim the cult of productivity pervading America. When I promote productivity as a good thing, I do not mean you should prioritize your job unduly. My notion of productivity contrasts with consumption. Productivity in the sense of “having a job” is, in fact, consumptive, as opposed to “doing work.”

Language reflects the monopoly of the industrial mode of production over perception and motivation. . . . People who speak a nominalist language habitually express proprietary relationships to work which they have. All over Latin America only the salaried employees, whether workers or bureaucrats, say that they have work; peasants say that they do it: “Van a trabajar, pero no tienen trabajo.”

Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (1973)

(Do not be fooled by Illich’s contradistinction between salaried workers and peasants; his predictions of the encroachment of consumerist society into even the non-salaried classes have certainly come to pass in the age of ubiquitous smartphones.)

I envision a departure from consumerist framing of work, towards a reconfiguration of productivity as a convivial expansion of creativity, to include prosocial (but not conventionally or entirely “creative”) activities such as teaching and other forms of service.

# Seasonality

It’s trivially obvious to me that winter is a season about structure, while spring is about whim.

Upon inspection there are fractal subtleties to this. Spring feels whimsical only because there are structured events organized to provide opportunities for whim. And winter is structured in the sense we plan carefully and take our days routinely, but between the structures of those routines and the long hours spent inside without the option to frolick outdoors comfortably, there opens the possibility of a different whim, the straggler’s whim, the endlessly-extended hangout borne from the circumstance of having nowhere to be anytime soon.

So here is another case where the dichotomy relates structure and whim as directly proportional; in other words, structure provides the possibility of whim. (Surely when events are too structured, whim does not emerge.)

Then again, winter is when all the event planning and preparation happens, so in spring and summer we can frolick whimsically. It’s a matter of perspective.

# Biking

Cars operate on the (infra)structure of roads. It is hard to achieve whimsy in a car between traffic and parking and lanes…

Bikes also require some (infra)structure but certainly less. So they are more whimsical.

# Physics: universal structure or divine whim?

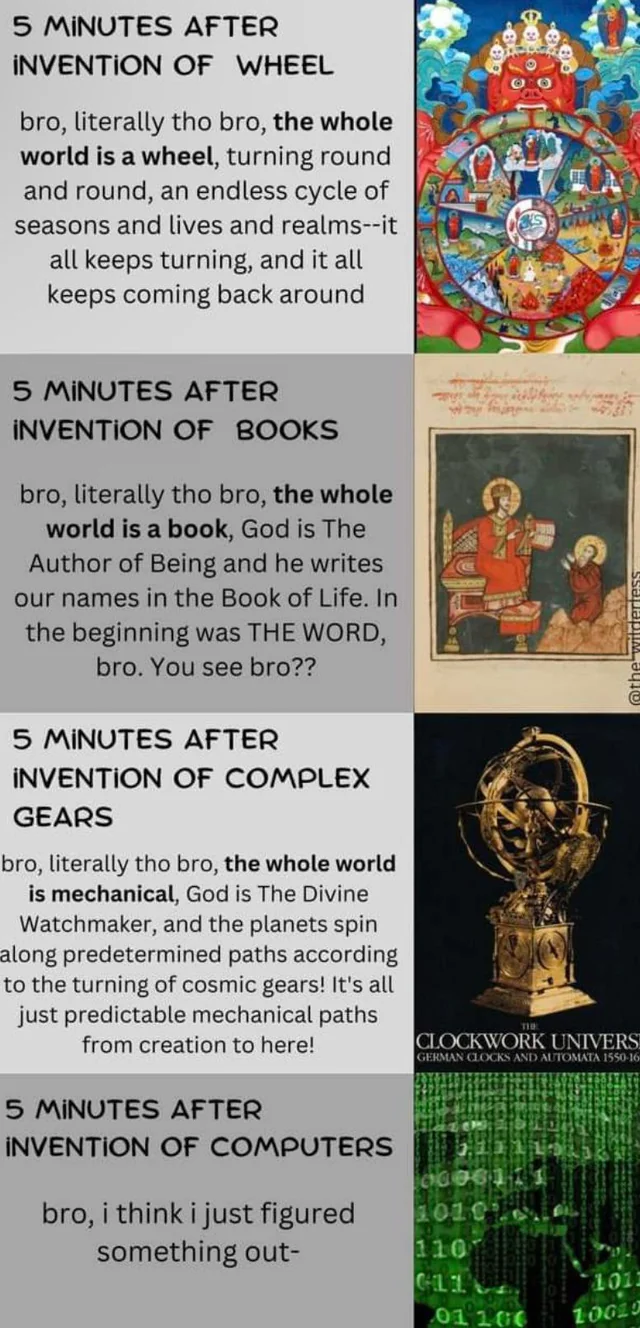

This dichotomy between structure and whim challenges our understanding of nature. Society seems to take it for granted that physics—indeed all the natural sciences—obey coherent scientific laws which can be rendered in mathematics. That this has worked so far—even as there remain vexing mysteries in cosmology, nuclear physics, consciousness, and the foundation of mathematics itself—is really a miracle and we would do well to appreciate that more often.

For most of human history (“since the dawn of time!”), philosophy and theology have spent significant effort grappling with the assumption that the universe is inherently unknowable, and then a couple hundred years ago we all started to realize you could measure and calculate a lot of things, and you can use those calculations to build tools that measure and calculate more precisely and more accurately, and so on. And then Darwin killed God, Oppenheimer harnessed the power to destroy worlds, we started to do scientific eugenics, etc. etc., we all know the story and its consequences. So now we all live in an enlightened world of reason, and all great advancements in science and technology exploit the knowable structure of the universe, and science is a process, so this train will just keep on going until we know everything, control everything.

But then what happened to the conception of the unknowable universe? And how exactly did we start believing in science?

I’ve hard it argued that religion was invented to provide explanations for natural phenomena before science was discovered. Thus casting science as the conclusion to a much longer dark age of reason. Supposedly, science closed the lid on these old myths, the ones involving a whimsical God who works in mysterious ways. Turns out that was just ignorance. Now that we have science, we don’t need religion. Even your spiritual needs can be upgraded into behavioral psychology, made manageable with modern medicine, since humans are animals after all, biological machines that can be mechanistically understood and repaired and improved.

It’s compelling, this story of religion. Belief in a higher power was just a stepping stone in anthropological history, but from the moment we discovered fire we have been on a path to greater and greater knowledge and power, thanks to our love of reason. And it explains why science seems to be getting stronger while religion gets weaker. If religion was always just a crude attempt to understand the natural world, of course it has evolved to fit the times. Of course we have replaced trickster deities with benevolent Abrahamic Gods who bestow upon us divine knowledge of nature and promote reason and structure. The idea (the hope) that the universe is knowable has always been there, just hidden, inaccessibly, in the Godhead, until Socrates and St. Augustine and Einstein 1 revealed the path. Some version of this is embedded in most world religions. But religious thinking does contain an unalienable core of faith, which is why we have to move beyond it and truly embrace science.

So that is the story of religion that science has retroactively applied to human history. Let us now consider the story of science.

That the history of science portrays frequent, radical refutations of widely-accepted theories does not contradict the idea of a structured universe. This story of scientific discovery upholds the validity of the scientific method, the idea of a convergence on ground truth. Typically it presumes that such a ground truth exists in the sense that scientific models can explain and predict natural phenomena, and at the very least it shrugs its shoulders at the notion of fact, saying that scientific laws by definition only approximate empirically, and that science has no opinion on the existence of a fundamentally fathomable universe. Either way, you operate on the assumption that it works—and it does work! My question is: aside from the empirical evidence for the effectiveness of empirical evidence, why do we (epistemologically, morally, aesthetically) believe the universe has structure in the first place? 2

Of course not everyone seems to want to believe this. For

one thing, the dominant contact point between science and society these

days is machine learning: a discipline whose most successful

technologies are fundamentally unknowable, each decision from a language

model comes from a “black box.” Or there’s problem that arise in a

purely formal setting, such as P vs NP in

computational complexity, which has the appearance of resisting

apprehension without explanation, except that it feels right

that they are unequal. Another: in the more speculative parts of

physics, you find quasi-scientific reconfigurations of the character of

a capricious God, like the notion that universal constants may change on

us, rendering all our empirical efforts pointless in the face of a

greater logic, one that may remain incalculable. Whether it emerges out

of religious inspiration or inconsistencies within our scientific

theories, there’s something alluring about universal whimsy.

And yet even the idea of an inconstant universe can be fathomed

scientifically, like theories of time-varying

universal constants. Complexity theorists’ inability to resolve

P vs NP may just indicate the immaturity of

our theory of complexity. And on the matter of artificial intelligence,

I have colleagues working hard to apply the science of uncertainty to

machine learning, so we may understand them yet again—albeit in the

regime of probability and statistical inference, the newest turn of

science, guesswork made rational through mathematics, an evolution which

seems to not merely extend science but recontextualize and recast

science itself as a stochastic process. An explanation for everything.

At every dead end, a new unifying theory.

So the disagreement on this point, on whether nature is fundamentally structured or fundamentally whimsical, rages quietly, surfacing only indirectly, as debates over whether it is even possible to resolve certain questions in our current frameworks, because the cult of rationality has placed a taboo, not on not knowing, but on not being able to know.

Last year we saw the release of Nosferatu, representing our fear—our reluctant awareness—that there are places in which current science holds no power, that there are things about reality that only the occult manages to provide answers, due to a fraught social epistemology of not-knowing or science’s inherent limitations…. Cinema, with its remarkable ability to reflect the historical consciousness, proves that we remain irresolute over the question of natural reason. The universe is calculable—we know this empirically—but why is it calculable?

E put it like this: in the year of our (empirically fathomable) lord twenty twenty-five, the essential question of religion and philosophy is simply whether you believe in a materialist or non-materialist basis—basically, does spirit precede expression, or does spirit emerge from expression?

Our spirit of reason (the belief in a rational world), our expression of technology (exploiting universal structure). Layering this over our story of science as the incremental evolution of empirical knowledge from basic observation to sophisticated engineering, it seems that the materialist basis is straightforwardly correct, and the other violates causality. “Surely,” says Heidegger, “technology got under way only when it could be supported by exact physical science.” Indeed that is chronologically true, but it misses the historical truth.

Modern science . . . pursues and entraps nature as a calculable coherence of forces. Modern physics is not experimental physics because it applies apparatus to the questioning of nature. The reverse is true. Because physics, indeed already as pure theory, sets nature up to exhibit itself as a coherence of forces calculable in advance, it orders its experiments precisely for the purpose of asking whether and how nature reports itself when set up in this way.

Martin Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology,” in in Martin Heidgger: Basic Writings, ed. David Farell Krell (1977)

While this idea is hardly surprising, it poses again the question: why would physicists approach nature as a “coherence of calculable forces”? Though it arrives at universal reason, early science is moved by faith. “Modern physics is the herald,” Heidegger writes, “whose origin is still unknown.” Here, “origin” refers not to the literally earliest conception of the idea, but the rational basis for it, even if applied retroactively.

Was science handed to us in a Promethean sense? Is it totally contingent that we happened upon the keys to understanding the universe? Is it inevitable, extrapolating from the course of anthropological development, as we settle into agricultural societies and invent money, which must be counted and calculated, giving us the conceptual tools to measure, which are then reappropriated by curious proto-scientists who, both well-fed and unburdened thanks to agrarian surplus, are free to ponder the mysteries of nature? Is it built into our biology? Or is it proof of our divine spark, revealing the inner fire leftover from creation: something that we chose of our free will, not merely accepting but earning the fruits of technology?

A simple answer: science is only useful if it subscribes to reason.

It is, as Schrodinger has remarked, a miracle that in spite of the baffling complexity of the world, certain regularities in the events could be discovered. One such regularity, discovered by Galileo, is that two rocks, dropped at the same time from the same height, reach the ground at the same time. The laws of nature are concerned with such regularities.

Eugene Wigner, “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences”

This is practically a matter of semantics. We have defined science as the domain of making predictions based on reasonable assumptions of structure. And yet the miracle:

The enormous usefulness of mathematics in the natural sciences is something bordering on the mysterious and that there is no rational explanation for it.

In other words, the fact that science works is the mysterious part. This hole at the center of our rational donut is serious enough that an entire field, philosophy of science, concerns itself with it. But that field, too, rests on structure of a different kind: philosophical structure of argumentation, perhaps less compulsively rigorous than mathematics but not so different in its logical motions, especially in the analytical parts.

It is either a natural inevitability or an incredible stroke of luck that we have mathematics. Structure or whim. The more you believe in the structure, the more you start to know. Can whim tell us anything at all?

The great danger

In whatever way the destining of revealing may hold sway, the unconcealment in which everything that is shows itself at any given time harbors the danger that man may misconstrue the unconcealed and misinterpret it. Thus where everything that presences exhibits itself in the light of a cause-effect coherence, even God, for representational thinking, can lose all that is exalted and holy, the mysteriousness of his distance. In the light of causality, God can sink to the level of a cause, of causa efficiens. He then becomes even in theology the God of the philosophers, namely, of those who define the unconcealed and the concealed in terms of the causality of making, without ever considering the essential provenance of this causality.

In a similar way the unconcealment in accordance with which nature presents itself as a calculable complex of the effects of forces can indeed permit correct determinations; but precisely through these successes the danger may remain that in the midst of all that is correct the true will withdraw.

Heidegger, ibid.

Or a great possibility? Someone on Twitter wrote:

re-enchant the world? algorithmic society is completely agnostic to causal logic. it is entirely about correlation (i.e. you will like this song because people like you liked it, there is no “reason” per se). we are returning to magical thinking, anthropologically speaking

Such a perspective ignores that the data schema of the dataset from which the machine learns is structured by humans, embedding our rational biases. There really is a “reason,” even if the reason is obscure—it’s just very high-dimensional. An odd arrangement: the reason is somewhere in the data, but inaccessible, like divine knowledge, except in a reversal of the traditional view of God’s relationship to humanity. Here, we create the world and god-in-the-machine is the consciousness interpreting it.

Other remarks

- Structure, in the sense of a system being composed of isolated subsystems, and the hope or faith or assumption that it exists and can be understood, is the basis of Lio’s “Carving Nature at Its Joints”.

- My friend A said “nature is my religion.” She believes in inherent structure, but she isn’t convinced our scientific methods are good at uncovering it.

- Katy’s new book of poetry uses an algorithm to arrange the poems in a unique order in every printed copy. She designed it to facilitate whim—serendipitous connections between poems based on relationships and harmonies that emerge from prosody and randomness rather than from chronology.

- Carl Sagan, in The Demon-Haunted World, is terrified of returning to the so-called dark ages where we consult horoscopes. Do horoscopes presume a structured universe, even if the structure is empirically wrong?

- Arthur Rimbaud disparaged the “mad statistic” that reduces our lives to numbers and calculations.

That’s all I have for now.

Carmel

Let us also add John Stuart Bell, who proved that in fact there are no hidden variables, God really does not keep a divine ledger to be consulted at every wave-function collapse. God really does play dice with the universe! Yet even this does not contradict the idea of a structured universe in the mind of the scientist.↩︎

Embarrassingly, I still haven’t read Hume’s work on the problem of induction. It sure would make me look a fool if I read him and found all my thoughts trivialized…↩︎